The city of Poseidonia rose on a low, almost completely flat limestone plateau, close to the coastline, from which a sandy dune separated it, and from a swampy area to the north-west which led to its unusual bend in the line of the city walls. The limits of its “chora” were very well defined by the geography of the district, bordered to the north by the Sele river, which acted as a border with Campanian Etruria, to the east by the Alburni Mountains and to the south by the Agropoli promontory, which closed the Gulf of Salerno. (1)

In the absence of explicit literary traditions, its foundation is placed around 600 BC thanks to archaeological data from the urban area and from the grandiose extra-urban sanctuary to the mouth of the Sele river dedicated to Hera, the great divinity of the Achaeans.

Strabo (VI, C252) wrote that Poseidonia was a true subcolony of Sibari, without mentioning the oikistes (see Note). Moreover, the same Greek historian and geographer specifies that his foundation was preceded by a fortress on the sea (tèichos epithalàssios), probably Agropoli. This is the first Greek foundation along the Tyrrhenian coast between Cuma and the Strait of Messina, followed by other foundations and foundations during the first half of the 6th century BC (cnidia Lipàra, Medna and Hippònion subcolonie di Locri, the Laos and Scidro problems, attributed to Sibari, la focèa Velia).

The geographical position of Poseidonia had great advantages because it arose:

1. In the extremely fertile plain of the Sele, south of the river of the same name

2. In front of the rich and powerful Etruscan city of Pontecagnano, as an outpost at the north-western end of the vast “Sybarite empire”

3. Not far from the territory of the Enotri towards which it becomes privileged mediator. (2)

Since its foundation, the Achaean subcolonia has been carving out its large portion of very fertile territory, extended along the coast from the mouth of the Sele river, to the north, up to Agropoli, to the south, and inland for the entire flood plain. to the slopes of the hills to the east. The “chora” of Poseidonia is soon bordered by sanctuaries: first of all the great Heraion at the mouth of the Sele river, but then also the more modest places of worship of Albanella, Fonte di Roccaspide, Capaccio, Acqua che Bolle, up to the sanctuary of Agropoli, which some want to attribute to Poseidon Enìpeo. (3)

Since the first decades of life, Poseidonia shows an astonishing urban and architectural development, comparable only to the same time that occurs in Selinunte, also a frontier foundation (of Mègara Iblea), and in Syracuse. (4)

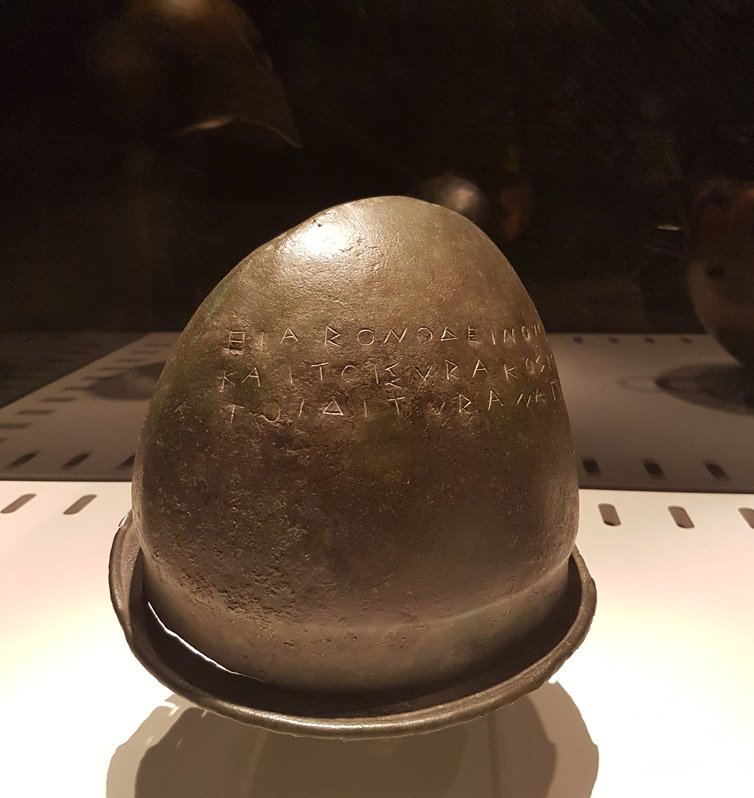

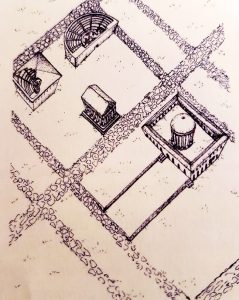

Since the foundation the vastness of the public spaces reserved for the gods and the meeting place of citizenship stands out: the whole central strip of the city, for a width of 300 m and a width of about 900 m, from the Porta Aurea to the north up to the Porta Giustizia to the south, it is destined for the agora square and the two great urban sanctuaries, soon monumentalized, such as the Heraion of the Sele river, through the construction of imposing sacred buildings. Poseidonia together with Metaponto, despite all the urbanistic and chronological uncertainties due to the successive phases of life that have erased most of the oldest settlement fabric, are the best known cases of archaic urban plants, the result of a careful planning of the spaces and their rational distribution. (5)

NOTE: The individual chosen by an ancient Greek polis (town) as the leader of any new colonization

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Giocacchino Francesco La Torre, Sicilia e Magna Grecia, Editori Laterza, 2011 pp 195-196

- Ibidem, 53-54

- Ibidem, 89

- Ibidem, 53-54

- Ibidem, 196

For further info about our Paestum and Buffalo mozzarella farm tour