Cuma, the first “apoikìa” [from the verb “apoikèo” = “I live far away”] – Greek colony of the West, immediately after its foundation in the second half of the 8th century BC , expanded rapidly along the coast of the Gulf of Naples, founding fortress-ports, “epìneia”, such as Miseno, Pozzuoli, Pizzofalcone, Capri. It was a way to guard the territory and control it.

However, at the end of the 6th century B.C. Cuma also favoured the foundation of “Neapolis” (1), which was not only an emporium like many others, but a real city: this further expansion inevitably led to a clash with the Etruscans, another population which spread across the territory. From their cities in the Campania plain (Capua, Calatia, Nola) and the Salerno area (Pontecagnano, Fratte) they moved towards the coast contending with the Greeks the dominion over the indigenous people. (2) The naval battle of Cuma of 474 B.C. was won by the Greeks and it caused the beginning of the progressive decline of the Etruscans in Campania.

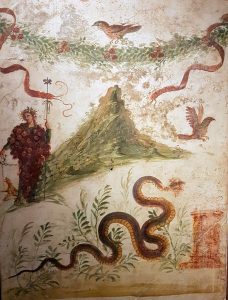

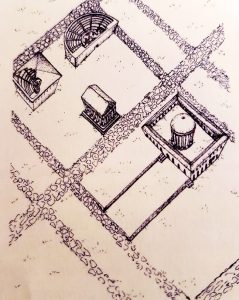

Although very little of the Greek-Roman “Neapolis” remains today, the historical center of Naples, entirely superimposed on the ancient city, has maintained its regular urban planning, articulated on 3 East-West “platèiai” [sing. platèia – main roads] and about twenty North-South “stenòpoi” [sing. stenòpos – secondary roads], forming rectangular blocks (35m x 160/180m). The city developed over about 70 hectares and was surrounded by gullies. It was also bordered by massive city walls of tufa blocks dating back to the 5th century BC, restored several times between the 4th century B.C. and the 5th century A.D. (3)

The very large “Agorà” [main square], was divided into two levels, separated by the median “platèia”, traced by the current “Via dei Tribunali”. This arrangement is known above all for the presence of remains of buildings from the Roman era, although it is a shared opinion that it may reflect a contemporary urban planning of the Greek Hippodamian style.

The upper agora, the mountain area, is characterized by the presence, of two big buildings for show side by side, the Theater and the Odèion (Small Theater). To the south is the great “Dioscuri” temple, also from the Imperial era, which dominated the median “platèia”. (4) Of this temple, two surviving Corinthian columns are still on the facade of the “Basilica of San Paolo Maggiore” in Naples.

The lower agora, however, narrower than the upper one, boasted the presence of the covered market and the shops of the Imperial era. The functional distinction between the two squares, which appeared evident in the Roman era, may have been realized as early as the 4th century BC, when the lower agorà assumed a commercial character, leaving the more purely political functions to the upper one. (5)

WHY IS THE HISTORICAL CENTER OF NAPLES SO INTERESTING ?

The historic center of Naples, entirely superimposed on the ancient Greek city, has perfectly preserved the regular urban planning of the Greek “Neapolis”, divided into 3 East-West platèiai (main roads) and about twenty North-South stenòpoi (secondary roads). The Greek city and, at a lesser depth, the Roman city are well preserved under the streets of the current historic center: in archaeological areas such as the excavations of the church of San Lorenzo, this phenomenon is very evident.

Furthermore, it seems that Akragas (Agrigento), in Sicily, was the only city of the colonial West to have developed duplication of the space destined to the ”Agorà” (main square) already in the classical era [480 B.C. – 323 B.C.], with a radical separation of administrative functions from commercial ones, according to a scheme which, in the motherland, took place in the late classical and Hellenistic period. (6). However, it seems that “Neapolis” soon followed the example of the illustrious polis (city) of Akragas, and this aspect is particularly interesting.

Bibliography:

1) See article: Daniela GIAMPAOLA, “Approdare”, pag 207, in Massimo OSANNA e Carlo RESCIGNO – Pompei e i Greci , Electa 2017

2) Stefano DE CARO “Le culture della Campania antica preromana: I I Greci (Pithekoussai, Cuma, Neapolis) in “Il Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli” – a cura di Stefano De Caro – Electa Napoli 1994. pag. 21

3) Gioacchino Francesco LA TORRE, Sicilia e Magna Grecia –– Editori Laterza – 2011 pag.210

4) Ivi, pag 260-261

5) Ivi, pag. 261

6) Ivi, pp. 258-260