It is indeed impressive to note that, twice in the 7th century BC and in the 15th century AD, almost the same region of central Italy, ancient Etruria and modern Tuscany, was the decisive hotbed of Italian civilization.(1)

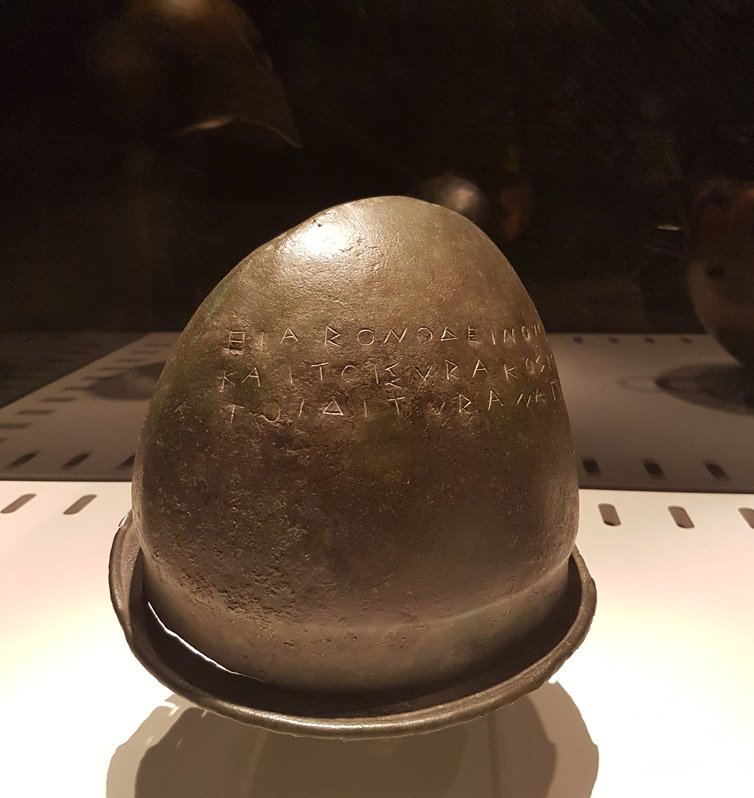

When in the VIII century BC the Greeks set foot on the coasts of Campania, they found it inhabited by populations who were different in language, customs and level of development, and they immediately established a relationship with them, now conflicting, now more or less friendly. The Greek historians of the Classical Age (480 B.C. – 323 B.C.), more attentive to the events of the Greek pòleis (cities), have told us little or nothing about these local peoples, who appeared to them barbarous and, therefore, devoid of history. Only two names have been handed down from these various indigenous peoples, the “Ausoni” and the “Opici”, sometimes assimilating them, more often distinguishing them. The “Ausoni”, of whom the “Aurunci” were considered to be descendants in historical times, lived between the “Liri” and “Volturno” rivers and were considered the first inhabitants of the region. “Opici”, on the other hand, according to some modern historians, would reflect a later reality, the so-called “Fossakultur” (Culture of Fossa Tombs) of the final Bronze Age (XI-X century BC) and of the early Iron Age (IX- VIII century BC). Of this period we have scarce archaeological evidence, above all the materials of the pre-ellenic necropolis of Cuma, the grave goods of the necropolis of the Sarno Valley (San Marzano, San Valentino Torio, Striano). On this indigenous substratum the “Villanovan culture” (from the burial ground of Villanova near Bologna which was first identified by Giovanni Gozzadini in 1853), that practiced cremation, developed. It seems that the “Villanovan culture” evolved a few centuries later directly within the Etruscan culture, which was certainly well distinguished also on the linguistic level by indigenous cultures. (2) It is important to underline that the “Villanovan Culture” practiced cremation: in this historical period – with the transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, which began at the beginning of the IX century. B.C. – the first distinction among the different peoples which draws our attention comes from the various funeral rites practiced . (3) Strabo wrote (4): ” The Tyrrhenians had twelve cities in Etruria, twelve of which they founded near the Po river, witness Livio (5), and twelve they founded in “Opicia”, whose capital city was Capua. (6) Capua is their metropolis, “head” of the others, according to the origin of its name. Since the others in comparison were small castles, except for Teano Sidicino. The Etruscan culture pervaded the entire interior of the Campania region, so that even the most peripheral Italic tribes, such as the Samnites of the interior, ended up assuming behaviors typical of the Etruscans, by considering the expansion of the more typical Etruscan products such as buccheri (typical Etruscan class of ceramics) and bronze objects. On the other hand, the same Greek border colonies such as Cuma and Poseidonia ended up receiving marked Etruscan influences, for example in the adoption of wooden architecture with terracotta decoration with bright colors. (7)

WHY ARE THE ETRUSCANS SO IMPORTANT TO UNDERSTAND THE ROMAN AND POMPEII HISTORY ?

The study of the Etruscans is fundamental for understanding the Roman world in general and Pompeii in particular. The Etruscan civilization had a profound influence on Roman civilization, later merging with it. The Etruscans were present in Campania from the ninth century, B.C. and it was probably these people who favored the foundation of Pompeii. With their synecism (see Note), they favored aggregation in a single city, Pompeii, of the mythical “Sarrastri”, a people who previously lived scattered in hut villages along the banks of the Sarno river.

NOTE:

Synecism = It was originally the amalgamation of villages in Ancient Greece into pòleis, or city-states

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

- Jacques Heurgon, Vita quotidiana degli Etruschi, Editore:IL SAGGIATORE 1967, p. 23.

- Stefano de Caro Le culture della Campania antica preromana: gli Etruschi, i popoli italici e le loro città da Il Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli – Electa Napoli 1994 pag. 33

- Gioacchino Francesco La Torre, Sicilia e Magna Grecia, Bari, Editori Laterza, 2011, pag 17

- Lib. V pag 373

- lib. V. C. 33

- Ibid.

- Stefano de Caro op. cit., p. 34

For further info about our guided tours of Pompeii and Herculaneum